Interviews

Production Design: From Analog to Digital to Built Environments and Back

Editor's notes

PRODUCTION DESIGN: FROM ANALOG TO DIGITAL TO BUILT ENVIRONMENTS AND BACK - by Vlad Bina, V.E.S.

Production designers and digital set designers

In 1977 William J. Mitchell (Computer-Aided Architectural Design [Van Nostrand Reinhold]) wrote that it will be a time when we won’t talk about “computer aided design” but only about design. So much the machines would become an intrinsic part of the process.

The “Internet Movie Database” describes a very clear if somewhat oversimplified chain of command for physical set production:

"Production Designer

An artist responsible for designing the overall visual appearance of a movie.

Art Director

The person who oversees the artists and craftspeople who build the sets.

Set Designer

The person responsible for translating a production designer's vision of the movie's environment into a set which can be used for filming. The set designer reports to the art director.”

Visual Effects are defined as:

“Visual Effects

Alterations to a film's images during post-production.”

This definition would have been probably correct a decade ago; since then several things have changed fundamentally in the way we design and produce a film. The common understanding is still that anything involving computers belongs to the “visual effects” department. On the other hand, everything dealing with analog art is assigned to the “production design” or “art” departments. The idea of computers and 3D in pre-production as opposed to post-production is nothing new though. 3D previsualization, for example, has been around for quite a while now and modern production design is using it as an indispensable tool. Still, when it comes to the division of credits, previsualization is still, probably because of the 3D involved, associated with visual effects and post-production. The same thing happens to digital sets.

During my 12 years of designing digital sets I encountered an unjustified divide between production design and art directors on one side and the digital set team on the other. If one looks closely at film production, a film appears to be assembled from two films: a real-set one with a production designer, set designer and art director and a virtual-set one with a digital set designer, matte painter and a color and lighting team. The swing gangs and set decorators are mirrored in 3D production by modelers and texture artists. The communication between the two departments is sometimes minimal. And still, the results of the two processes are two environments that need a perfect visual integration. The best way to achieve this integration is to merge the two design teams and use a coherent and complementary digital toolset from the inception of the film to final delivery.

Digital set design as well as previsualization are integral to the production design process and they should be considered as such. The result will be a better integration that will benefit the profession and streamline the journey of the moving image from concept to printed film stock.

Technical considerations:

Today’s production designers should understand the challenge of having to produce both a real and a digital version of their set, both of them perfectly interchangeable, allowing a wider range of camera choreography and post production work. Having only parts of a set built and the rest completed digitally is likely to become the norm.

The process of switching back and forth between digital and analog data as well as built and virtual constructs is still very complex and has to be organized better.

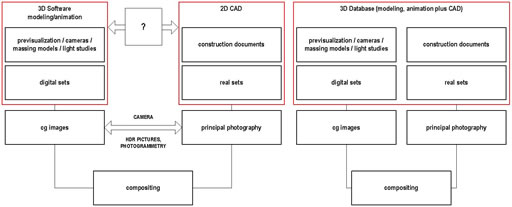

2d / 3d Integration

Re-building the digital replica of the set and camera tracking as well as the actual building of the real set will eventually be simplified by increased 2D/3D integration. This means compatible software (ideally, the same software) used to build both the real sets and the digital ones. Construction document production as well as camera and 3D digital models will be generated from the same program.

A central 3D database created in the initial stages of production can generate:

1. all the necessary elements for building the real set (2D documents, shop drawings, etc.)

2. the data necessary for the real camera choreography.

3. the precise 3D framework for the digital set production

The info can flow the other way too (from the real set back to the 3D database) in the form of photogrammetric or 3D scan derived adjustments. The 3D database thus becomes the pivot of the entire production.

The diagram bellow illustrates the advantage of having the entire process controlled within the same 3D software.

2d Documents From 3d Models

The “holy grail” of classic computer assisted design was always parametric generation of 2D documents from 3D models. You work on a 3D spatial construct, press a button and get dimensioned elevations, plans and sections -- essentially simple printable 2D vector data. Then, you adjust elements in the 2D drawings (some dimensions, for example) and the 3D model changes accordingly. Behavior intelligence is incorporated in the 3D elements – for instance, a door knows how to interact with a wall, a wall gets trimmed automatically when it intersects a roof, the elements obey standard dimensions, etc.

Things like these already exist in software packages used outside the film production world. In the construction industry, the current catch phrase is BIM (Building information Modeling) where software like Graphisoft’s ”Archicad” and Autodesk’s “Revit” are trying to coordinate the complex amount of construction document generation and subspecialty management from a central 3D database (the so called “virtual building”).

2d Documents From Maya

In film design and post-production work Maya is the software of choice; Also, 2D documents are still a must when set builders are involved. The question is: how do we bring 2D dimensioned drawings, ideally parametric in and out of Maya? Are we stretching Maya too much, requiring some minimal CAD capabilities from within the package?

The purpose, after all, is to build a real set identical to its 3D counterpart, without having to go back and forth too many programs. Maya is a solid animation software with very good camera controls and it is open enough to withstand necessary customizations. On the other hand, one can’t do film production compatible camera work in CATIA, Autocad or other CAD programs that come to mind. Conversely, one cannot do any 2D-3D parametric acrobatics inside Maya. It makes more sense, from a production design point of view, to build a 2D module on top of Maya’s 3D modeling capabilities, than a film compatible camera structure for a CAD package. The shape of things to come will be something close to a “CAD4Maya” menu tab within the modeling module or even an extra module similar to “Cloth” or “Paint”.

Bypassing 2d Documentation

With industrial robots, 3D scanners, 3D milling machines and all the high end technology involved in movie making, people might ask “Why can’t we just get rid of 2D documentation?”

Spatial design is different from object design and one cannot “mill” space the same way one would produce a toy. There is a new tendency, though, to use numerically controlled machines to produce the elements of the spatial structure, bypassing thus traditional 2D documentation. A good example is the architectural practice of Frank Gehry, one of the most prolific and original architects working today. Gehry shifted from traditional techniques to digital ones during the construction of his Art Museum in Bilbao. His digital production pipeline is discussed in Bruce Lindsay’s book “Digital Gehry” ( Basel: Birkhauser 2001); The sheer coordination effort necessary to generate the architect’s signature organic shapes, which, by their inherent nature, are hard to describe by typical construction documents, pushed Jim Glymph, Gehry’s digital alter ego, to look for solutions outside the profession. He came up with CATIA, a software used by aerospace engineers to precisely calculate, display and produce metal structures and finishes for airplanes. Working sometimes directly with milling machines and computer numerically controlled routers, Gehry bypassed shop drawings for steel fabrication and stone cutting. As Lindsey said “[we were] harkening back to medieval stonecutters under a tent on the new floor of the museum”.

In an ironic way the circle is closing between ancient methods and new technologies. Space design has known a variety of tools during its three millennia of existence. Computers are only the latest ones. They do not justify the artificial professional divide between two fields that are essentially identical in scope: production design and digital set design.

1. Full 3D sets

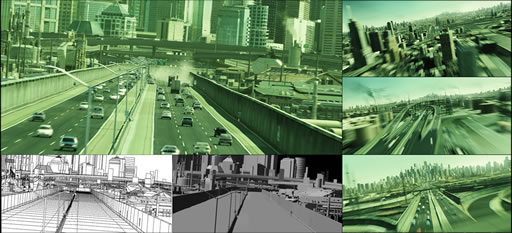

The Freeway Chase Sets in “Matrix Reloaded”

The freeway chase is a good example of the design process moving from the existing previsualization towards the final composited shot, with minimal involvement of real sets. The shot had 81 separate comp layers. The challenge was to integrate all the elements both on a 3D design level and especially on a color and lighting one. The textures were assembled from a multitude of sources and then synchronized with the color space and color depth of the Matrix principal photography plates. The objects were created in most cases based on photographs and hand drawn sketches, without any 2D software involvement.

The Megacity in “Matrix Revolutions”

For the aerial sequence, the main building block was a small area from downtown Sydney, amplified then to the size and the structure of a much larger city and textured with aerial pictures. The model was then rendered onto 6 digital hi-res tiles, that were in their turn re-projected on a hemisphere. There is a full correspondence between the 3D model and the projection, allowing us to generate in Maya the customary rendering passes for compositors: specular, fog, z-depth, y-depth, reflection and normal passes.

2. Set Extensions

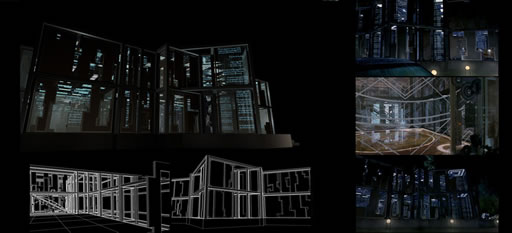

The Glass House In “13 Ghosts”

The film’s main set was a glass house with sliding panels, and lots of arcane mechanisms inspired by early 20th century electrical-mechanical devices, something between Nicola Tesla and Edison. It was built based on Sean Hargreaves’ design with an architectural studio in Vancouver. As in most cases, the set was complemented with a digital version. It was rebuilt in Maya and extended with an exterior shell and a set of sliding mechanical panels. The images show the final CG integration of the “13 Ghosts” production design.

3D Mona Lisa in “The DaVinci Code” teaser

The existing set was integrated with 3D models for seamless transition. Mental ray displacement and the modular structure of the digital set allowed for design flexibility and complex camera choreography. Both the real set and the digital one were coordinated at the same facility, allowing a perfect match.

Bibliography:

Lindsey , Bruce, “Digital Gehry”,( Basel: Birkhauser 2001);

Mitchell, William J., “Computer-Aided Architectural Design” (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1977);

Credits:

"13 Ghosts” Warner Bros. / Manex / Cinesite, 2001

"Matrix Reloaded", Warner Bros. / ESC Entertainment, 2002

"Matrix Revolutions", Warner Bros. / ESC Entertainment, 2003

"The DaVinci Code" teaser, Columbia Pictures. / Engine Room, 2005

About the author:

Vlad Bina trained as an architect and has been designing digital sets since 1995. His film credits include “13 Ghosts”, “Matrix Reloaded”, “Matrix Revolutions”, “Catwoman”, “Sin City” and “The DaVinci Code”.

About this article

In this Exclusive CGarchitect.com Article, Vlad Bina takes a look at the evolving digital set and production design workflows and the need for integrated software to steamline the design and visual FX pipeline.